There are very few places in the world as beautiful as the Tweed Valley. It has rugged volcanic peaks covered with one of the world’s few remaining subtropical rainforests. The swiftly flowing Tweed River, with its many small tributaries, winds through the wide valley and on out to the Pacific Ocean. Long, golden beaches stretch out north and south and the whole of this picturesque scene is visible from the top of Mt Warning/Wollumbin (with its awesomely eccentric profile, giving the Tweed a special character). [Note: the walking track to Wollumbin summit was permanently closed to visitors in October 2022].

There are very few places in the world as beautiful as the Tweed Valley. It has rugged volcanic peaks covered with one of the world’s few remaining subtropical rainforests. The swiftly flowing Tweed River, with its many small tributaries, winds through the wide valley and on out to the Pacific Ocean. Long, golden beaches stretch out north and south and the whole of this picturesque scene is visible from the top of Mt Warning/Wollumbin (with its awesomely eccentric profile, giving the Tweed a special character). [Note: the walking track to Wollumbin summit was permanently closed to visitors in October 2022].

From 1861 to 1880 the Robertson Land Acts opened up large areas of New South Wales for sale to small farmers. They could purchase up to 650 acres for one pound an acre. They were able to pay a deposit of two shillings an acre but had to fence and build on the land within two years. Joseph Stoker bought 600 acres at a place then marked as Dunbible Creek, a small tributary of the Tweed, in 1882. The nearest town was Murwillumbah with only a bush track for access. He tried cane farming for a while but after a decade he moved north selling his land to Arthur Byrnes.

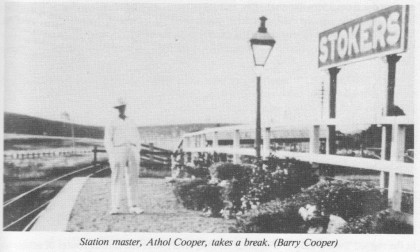

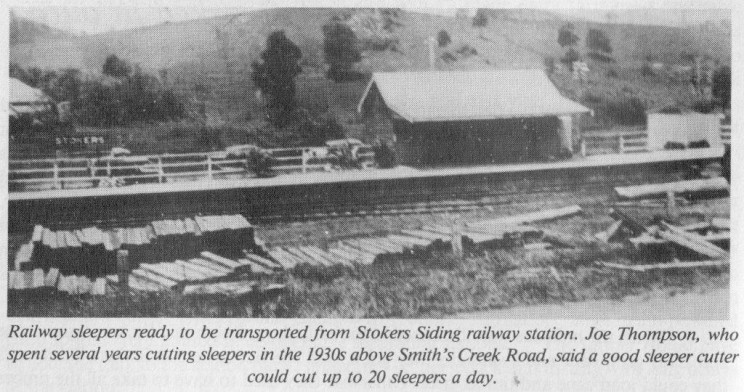

The village did not exist. The building of the train line through Byrnes’ property was really the first step. Other villages in the Tweed Valley had evolved because they were situated on the Tweed River, or deeper tributaries which could be used for transport. It was the meeting of the roads with the train line that gave birth to Stokers Siding. By 1894 the coach road which connected Byron Bay and Murwillumbah came in along the railwayline. Smith’s Creek Road came to the middle of the village and was a link with the village of Uki and other small settlements to the west. In times of flood it was easier to send dairy produce and timber from Uki to the train stop at Stokers Siding where it could be taken to Murwillumbah or Byron Bay.

The village did not exist. The building of the train line through Byrnes’ property was really the first step. Other villages in the Tweed Valley had evolved because they were situated on the Tweed River, or deeper tributaries which could be used for transport. It was the meeting of the roads with the train line that gave birth to Stokers Siding. By 1894 the coach road which connected Byron Bay and Murwillumbah came in along the railwayline. Smith’s Creek Road came to the middle of the village and was a link with the village of Uki and other small settlements to the west. In times of flood it was easier to send dairy produce and timber from Uki to the train stop at Stokers Siding where it could be taken to Murwillumbah or Byron Bay.

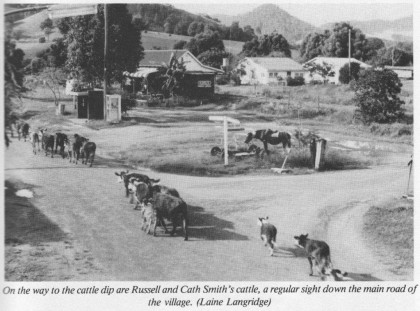

More farmers were settling around Stokers Siding. First they tried sugarcane farming but switched to dairying when a suitable grass, paspalum, was introduced to provide good pastures for dairy cattle. Settlers who ended up with steep land began growing bananas on the frost free slopes from about 1910 onwards. Meanwhile, farms were being established, men cutting down what seemed to be an inexhaustible supply of timber. Bullock teams dragged the big logs down from the forests to be loaded by gantry at the increasingly used train stop.

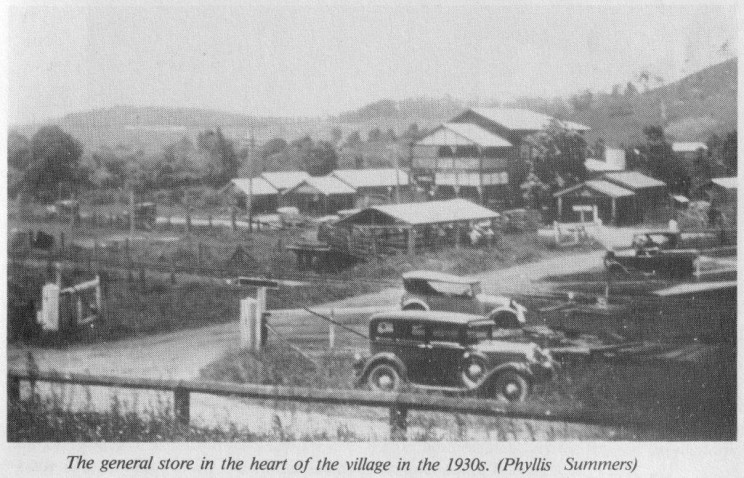

The train had been stopping to pick up passengers at Dunbible Siding since 1896. By 1905, when the gantry was built to load the timber, the name had changed to Stokers Siding. From this point forward the growth of Stokers Siding was assured. A travelling salesman from Griffith Brothers, Robert Miller, sensed an opportunity and built the first store right on the corner of Smith’s Creek Road as it crossed the railway line. He and his family moved in in 1909. In those early years the general beauty of the area must have been just a slight compensation for the lonely, hard-working days which ran into years.

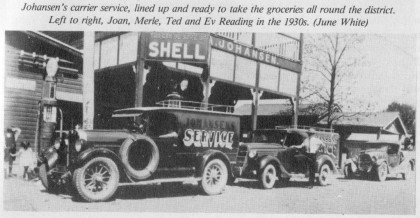

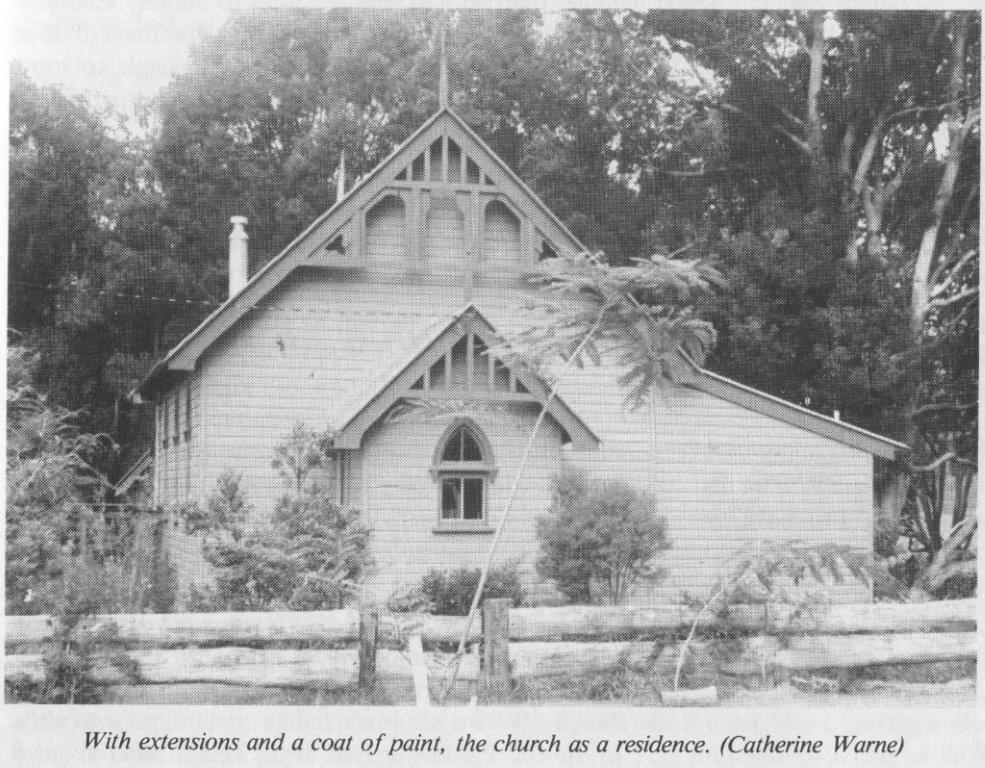

In 1914, when so many of the local men crowded the wharf in Murwillumbah, ready to set out on a journey to the muddy trenches of the horrifying war in Europe, there was little change for the people of Stokers Siding: 365 days every year, cows had to be milked and the banana patches tended. When the soldiers returned in 1918, Stokers Siding was linked to the outside world by telephone, there was a post office, a church, a hall and from 1917, a school. Reg Johansen decided to build a two-storey general store in the middle of the village which brightened the lives of the isolated farming communities and provided work for those who did not favour life on the farm. There were enough people around to form a cricket team, a vigoro team and to play tennis on a Saturday afternoon.

In 1914, when so many of the local men crowded the wharf in Murwillumbah, ready to set out on a journey to the muddy trenches of the horrifying war in Europe, there was little change for the people of Stokers Siding: 365 days every year, cows had to be milked and the banana patches tended. When the soldiers returned in 1918, Stokers Siding was linked to the outside world by telephone, there was a post office, a church, a hall and from 1917, a school. Reg Johansen decided to build a two-storey general store in the middle of the village which brightened the lives of the isolated farming communities and provided work for those who did not favour life on the farm. There were enough people around to form a cricket team, a vigoro team and to play tennis on a Saturday afternoon.

Between the wars hard times befell those living on the far north coast. The 1919 influenza epidemic carried off many, bunchy top killed banana crops in the 1920s and in the 1930s the Depression devastated the economy. Times changed. More cars and fewer horse-drawn vehicles travelled the still rough roads. In the late 1930s a new route for the Pacific Highway was started. It would follow the higher ridges east of the village and avoid the flood prone flat land that so often held up traffic heading north.

Although by 1945 there were picture shows in Murwillumbah as well as late night shopping to attract the crowds, the most popular form of entertainment was the local Saturday night dances. The Stoker’s dances were widely praised and they must have been good because in 1947 the hall from Dunbible was moved and added onto the front of the original Stokers Siding hall.

The new Pacific Highway was completed in 1954 and the constant flow of traffic now bypassed Stokers Siding. In the next decade there was a downturn in the dairying industry and by the mid-1960s many people had given up their farms or turned to beef cattle. Business also fell off for the general store. The final blow was in 1974 when the NSW State Rail Authority included Stokers Siding in its budget cuts and decided to let the train go through the village without stopping.

These events could have marked the end of the village’s growth but a new wave of people decided to move to the country. Mainly from the cities, often well-educated and with cars for transport, the new settlers could work elsewhere apart from Stokers. It still had all the benefits of a small village – a school, a hall, a church, a store and a post office.

It is true most Australians live in the cities but increasingly it seems there are things people feel the lack of in their urbanised lives. Perhaps it is in village life that we can experience the knowledge that we are part of a community and very much part of the land.

Images and text taken from “The Story of Stokers Siding” by Laine Langridge and published by Atrand Pty Ltd (now Kingsclear Books) with many thanks.

![]()